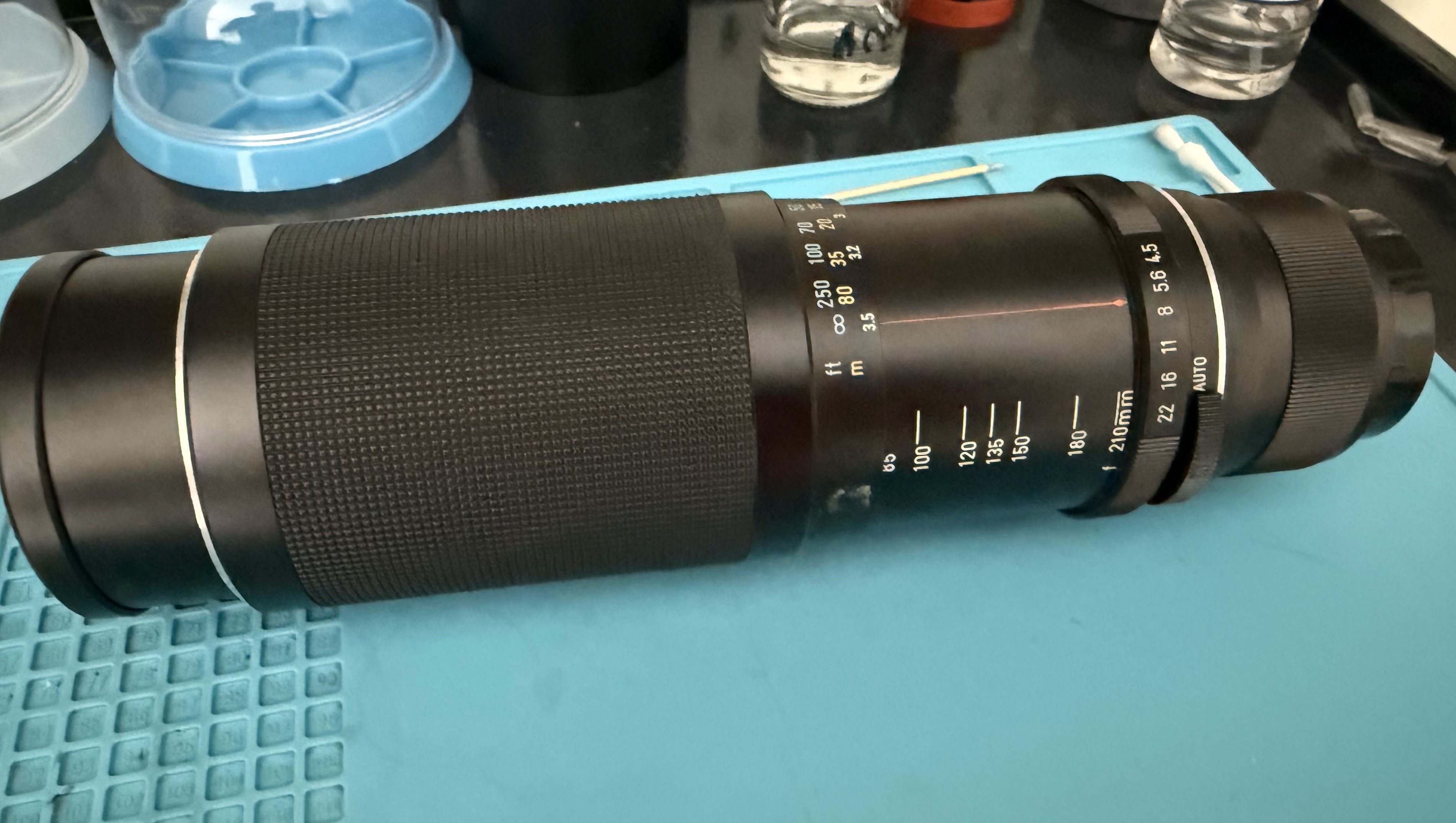

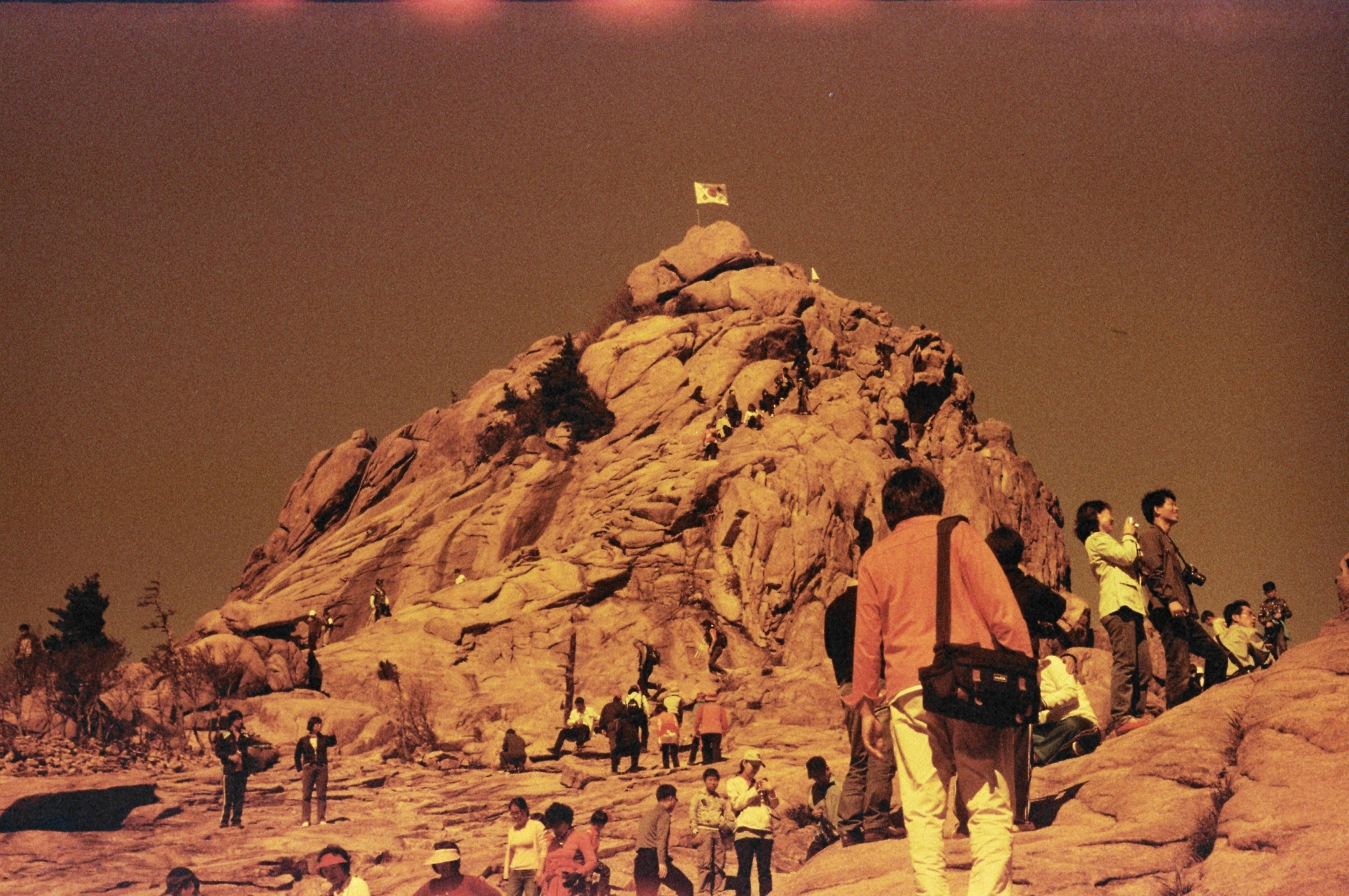

I picked up a near-mint vintage Asahi (Pentax) 135mm f/3.5 version 1 lens from Lucky Home (LH) Cameras, tucked away in the Miami Bayside Bangpu area of Bangkok. The place is a treasure trove of old and vintage Japanese cameras and lenses—though the pricing seems to depend entirely on the day you visit. When I dropped by on a Thursday, they were advertising a 70% discount across the board. Whether that’s a genuine deal or just a clever marketing ploy, I couldn’t resist. The lens was in beautiful condition, and at that price, it felt like a steal.

I snagged this Takumar lens for just 600 Thai Baht after the discount—roughly USD 18. A total steal, if you ask me. For a 65-year-old piece of glass, it was in surprisingly good shape: nearly mint, with only a hint of fungus and a slightly stiff focus ring. I scoured the internet hoping to find a disassembly guide, but came up empty-handed.

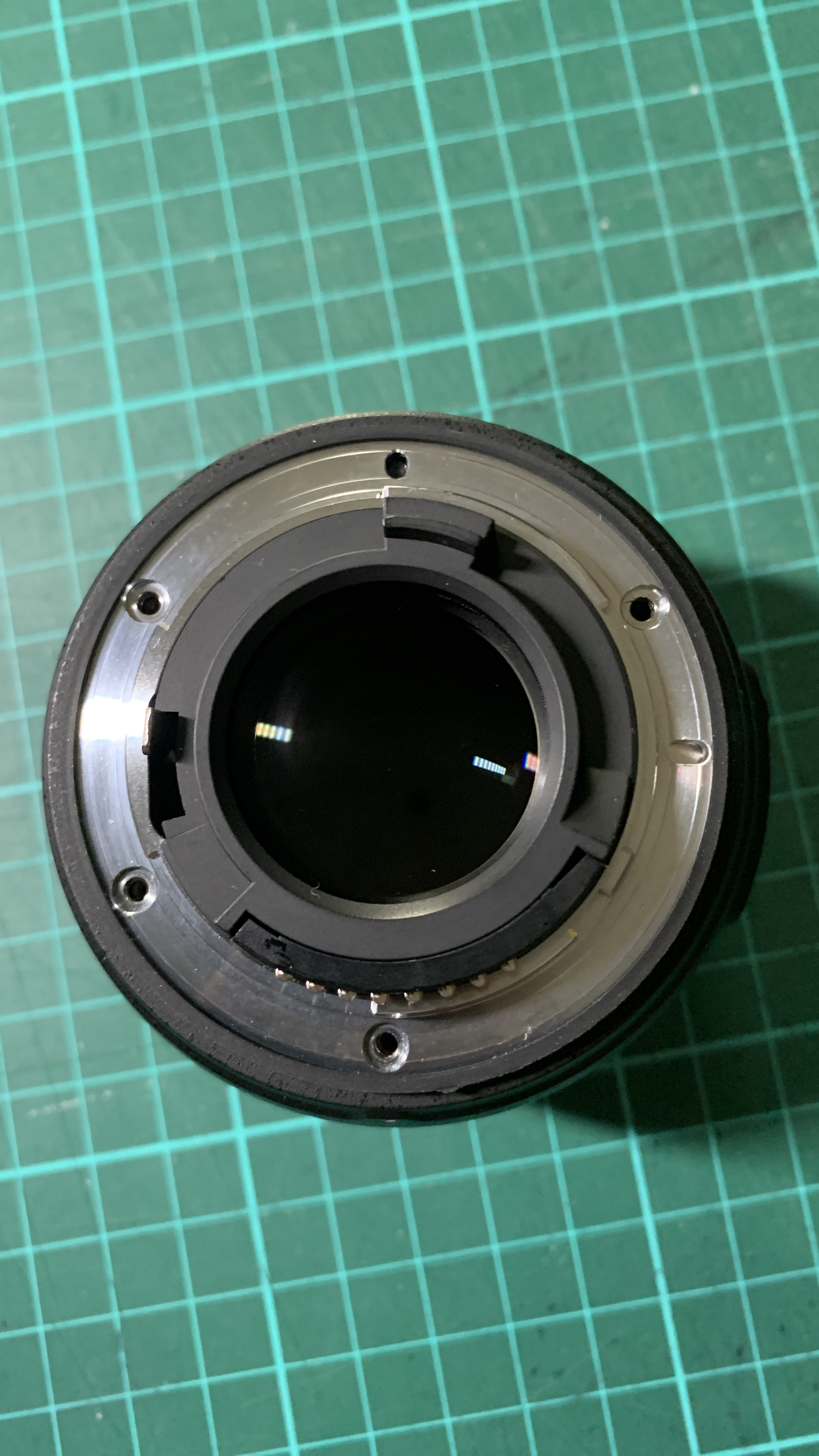

The build quality is impressive—classic Takumar craftsmanship. No visible screws anywhere on the barrel, save for three tucked away at the rear mount. It’s the kind of lens that feels like it was engineered to last generations.

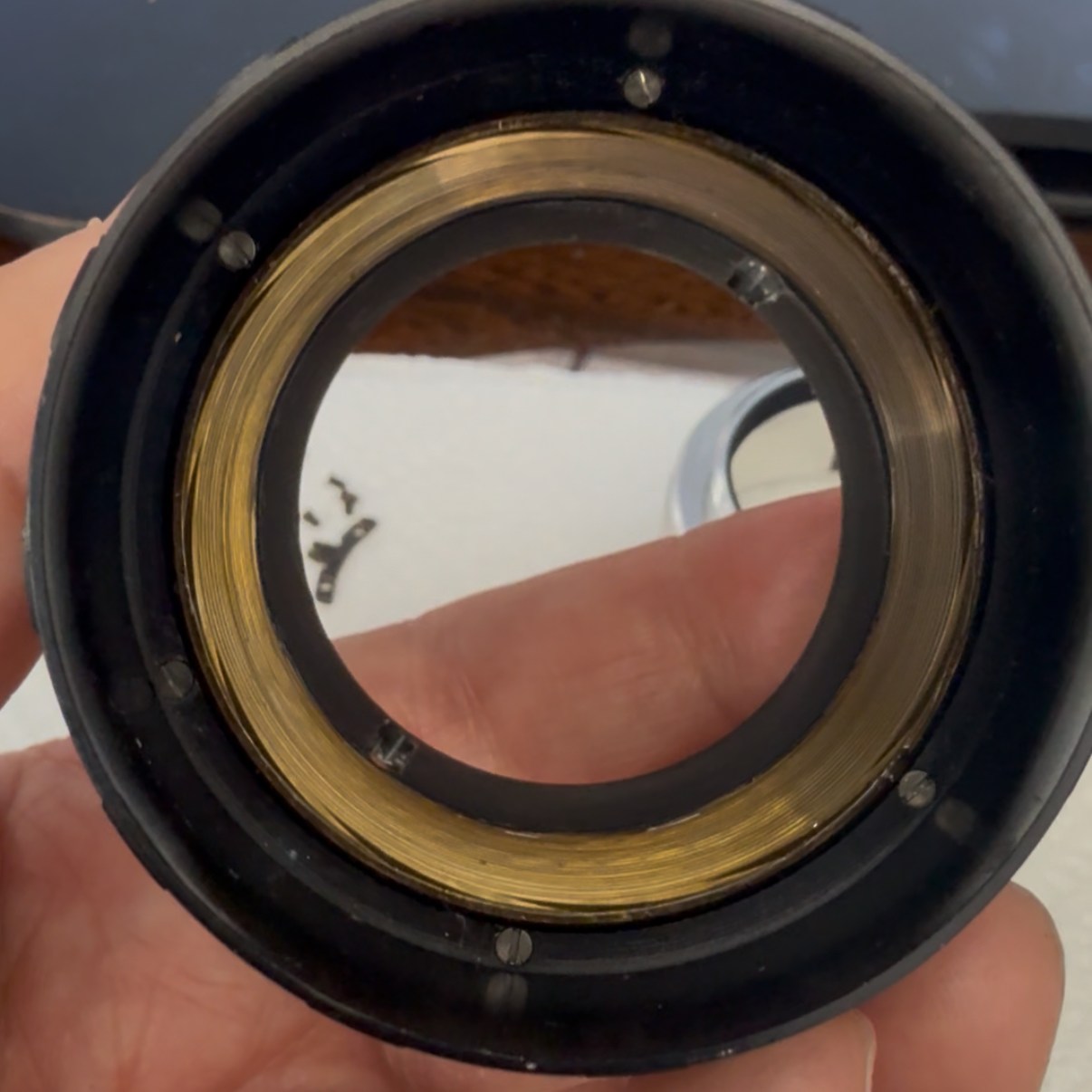

Removing the front elements is straightforward—just unscrew the entire front element group.

Next, detach the rear lens mount assembly by unscrewing the three visible screws located around the rear section. Once removed, the entire mount should lift off cleanly, giving you access to the internal components.

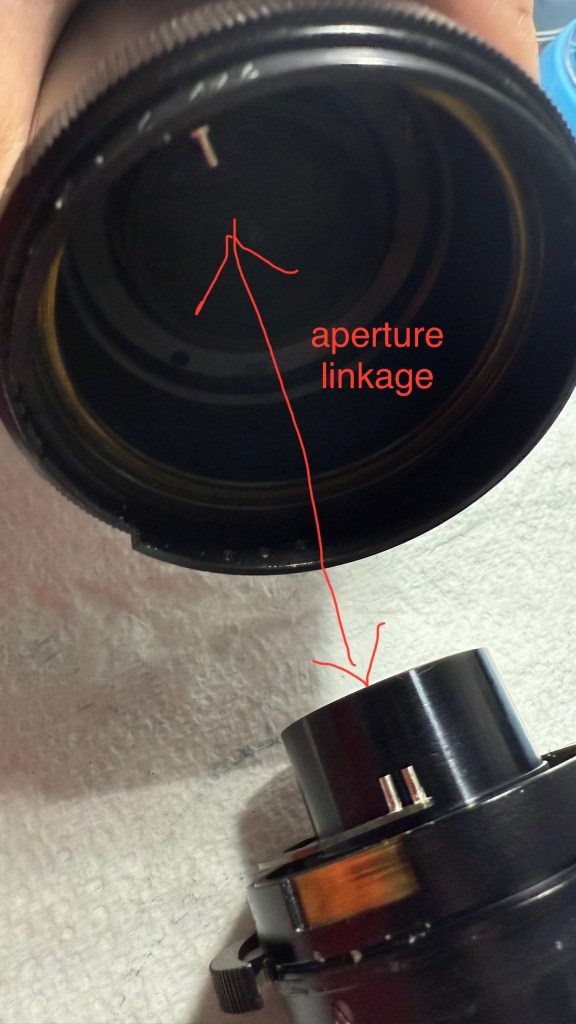

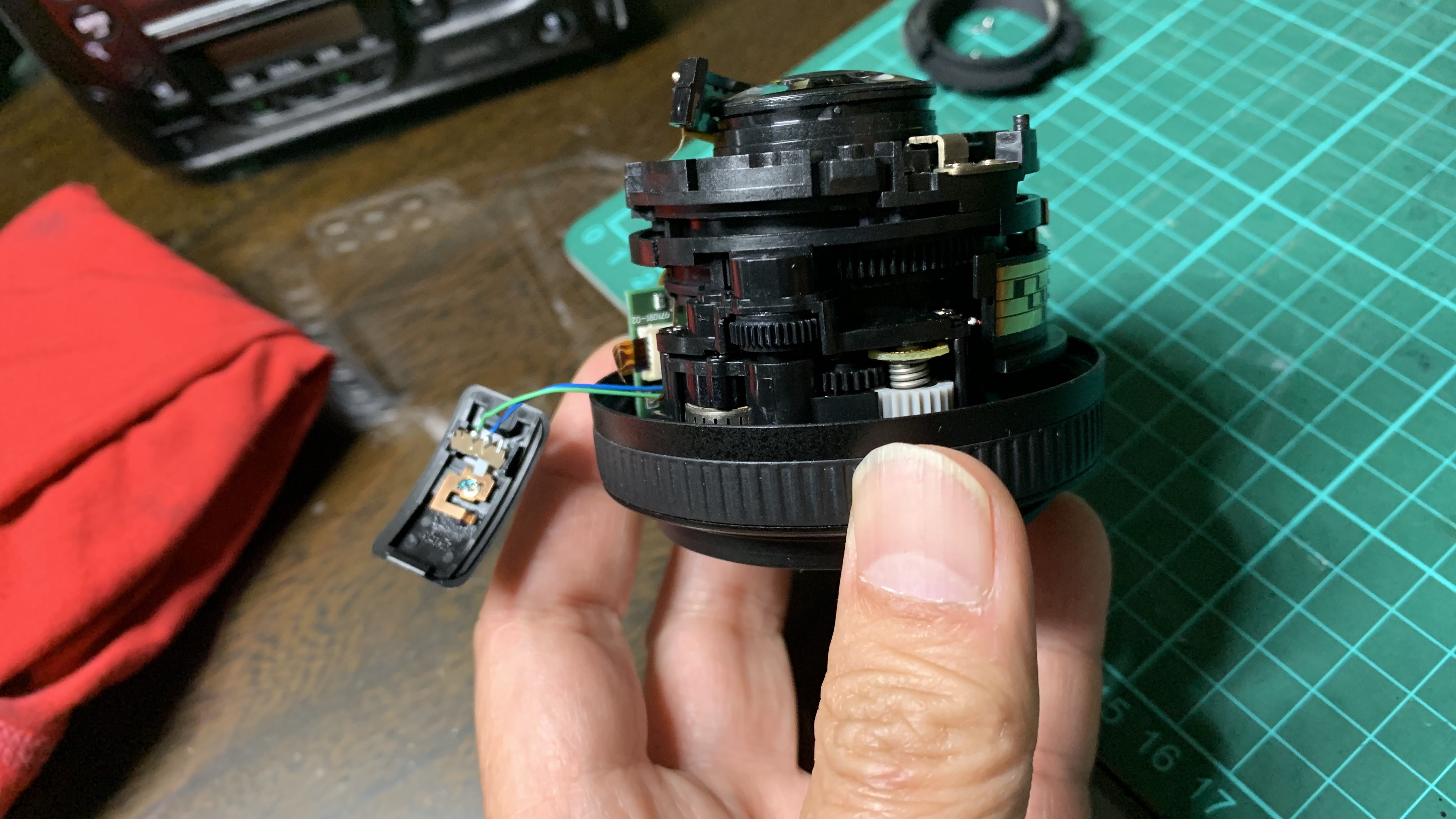

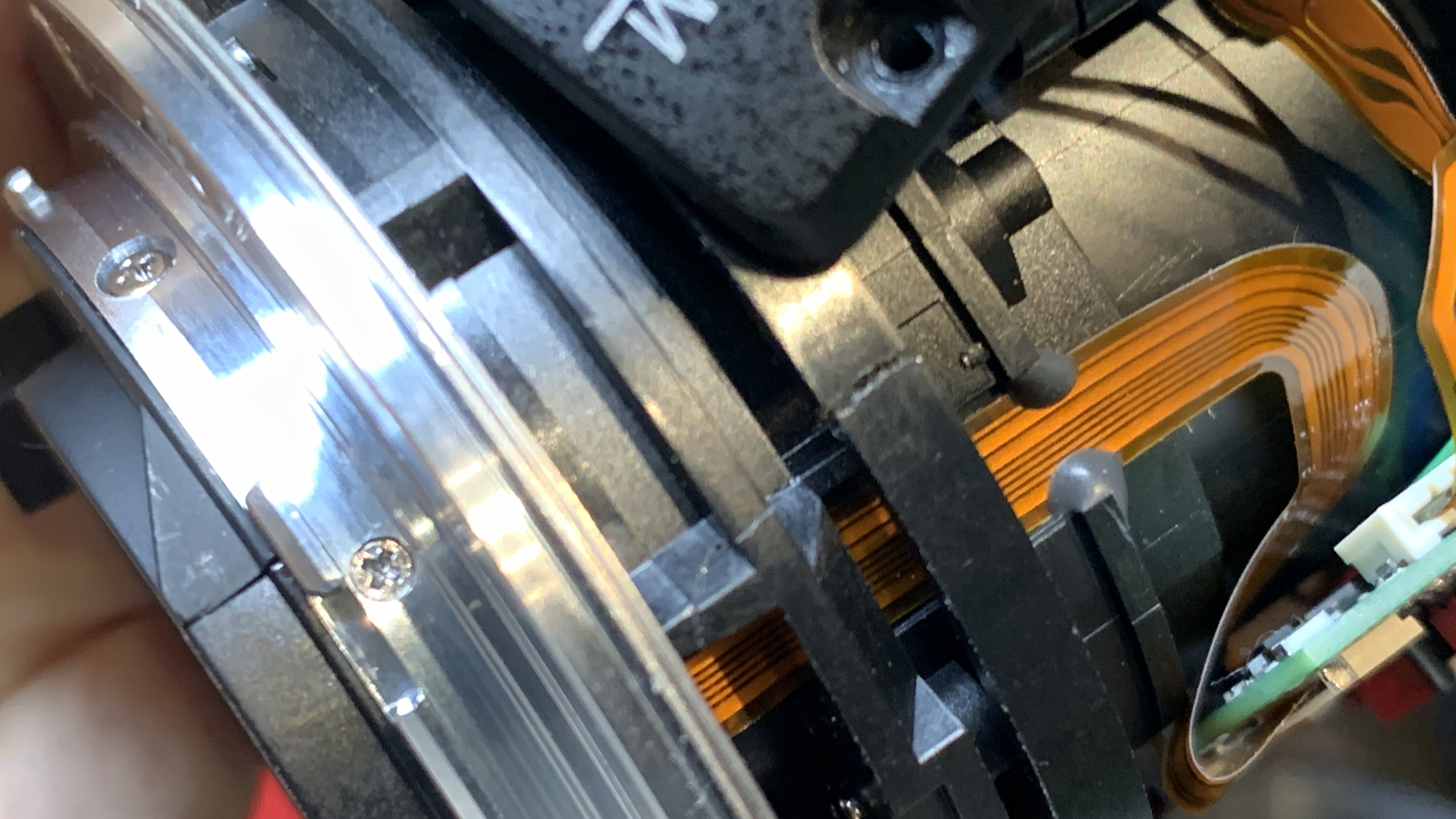

To remove the front pre-set aperture assembly, you’ll need to unscrew the two helicoid guide pins now visible from the rear. These guides secure the focusing mechanism and must be taken out to allow the aperture assembly to rotate out free. I chose not to remove the rear lens elements, as they were already clean and in excellent condition.

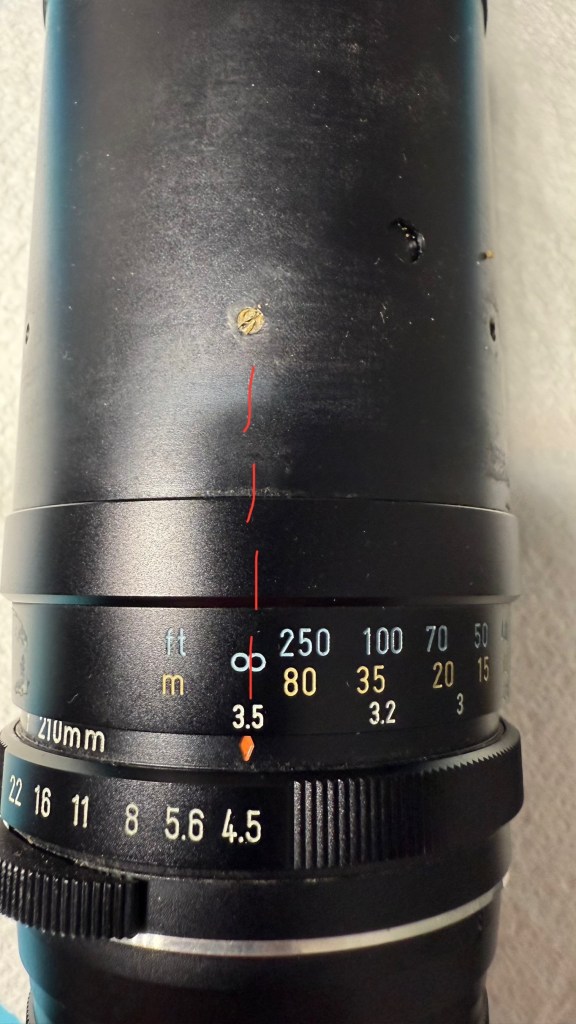

Before removing the helicoid guides, I carefully marked their positions to preserve infinity focus. I rotated the focus ring to the infinity setting, then scratched two faint reference lines where the tops of the guides aligned. These marks will serve as crucial alignment cues during reassembly, helping ensure the lens maintains proper focus calibration.

When removing the helicoid guides, make sure to note which guide fits into which groove. Each guide is slightly different, though the reason behind this design choice isn’t immediately clear. It might have been for fine-tuning focus alignment or simply a quirk of the manufacturing process. Either way, keeping track of their original positions is essential for smooth reassembly and accurate focusing.

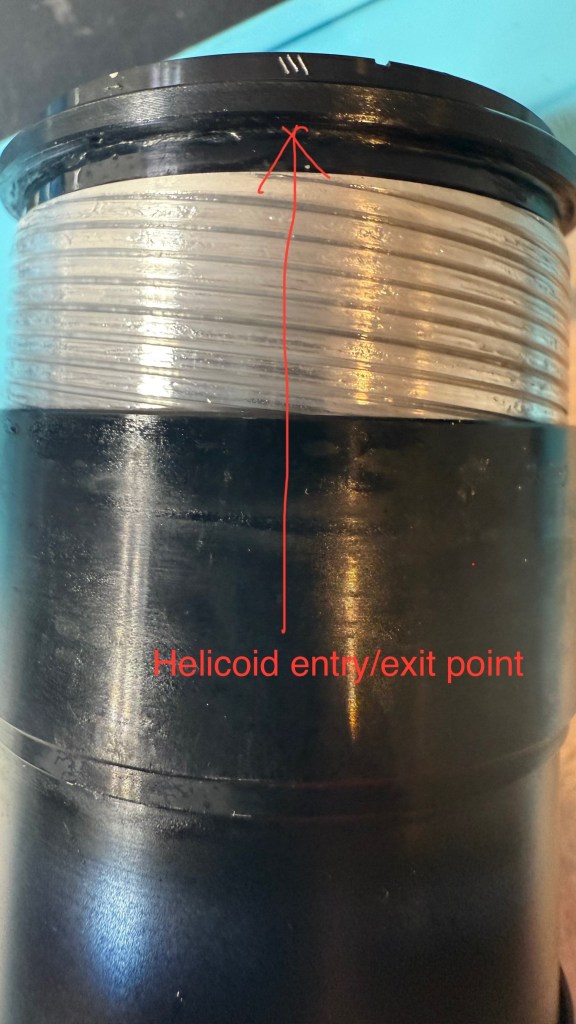

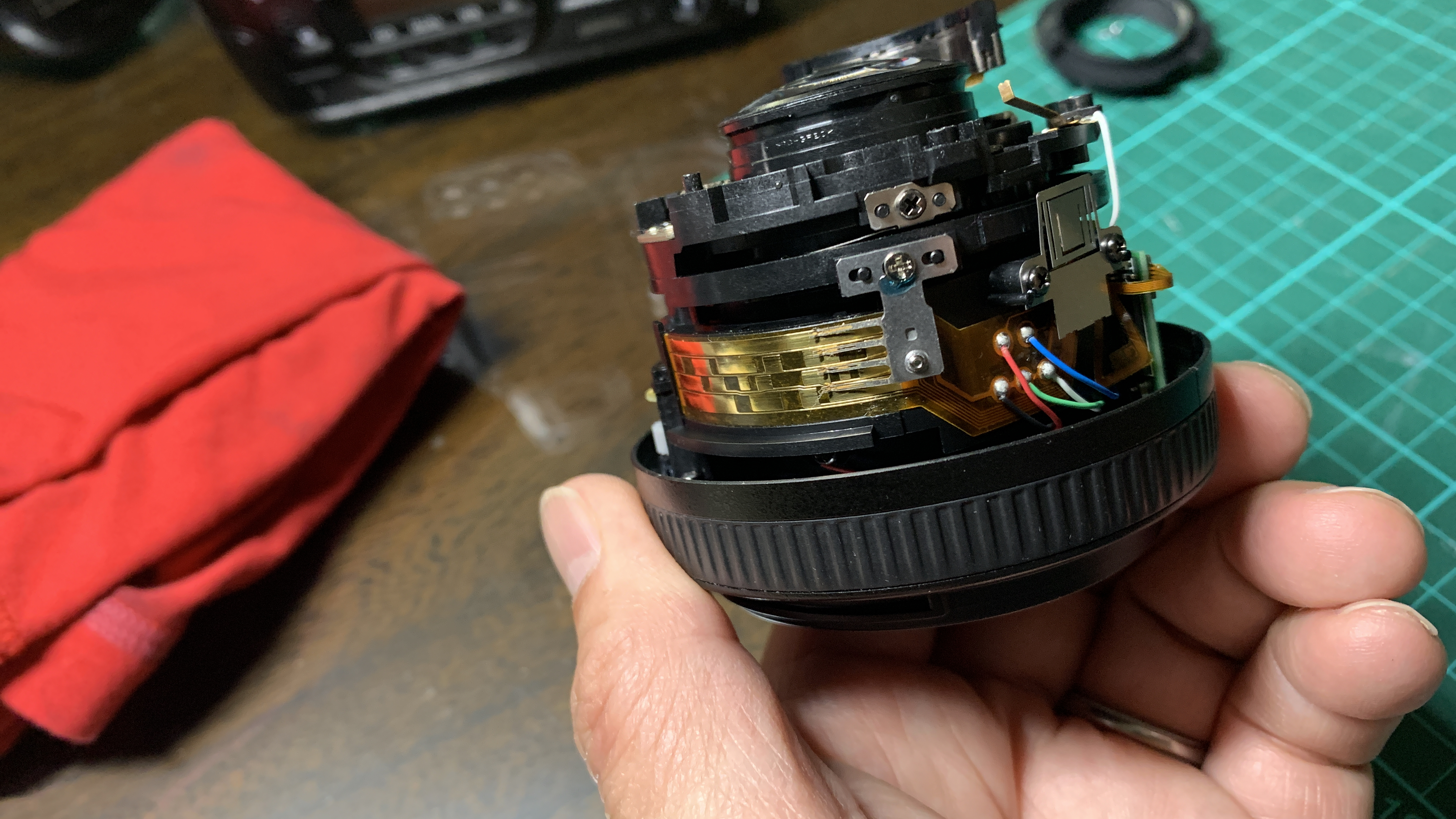

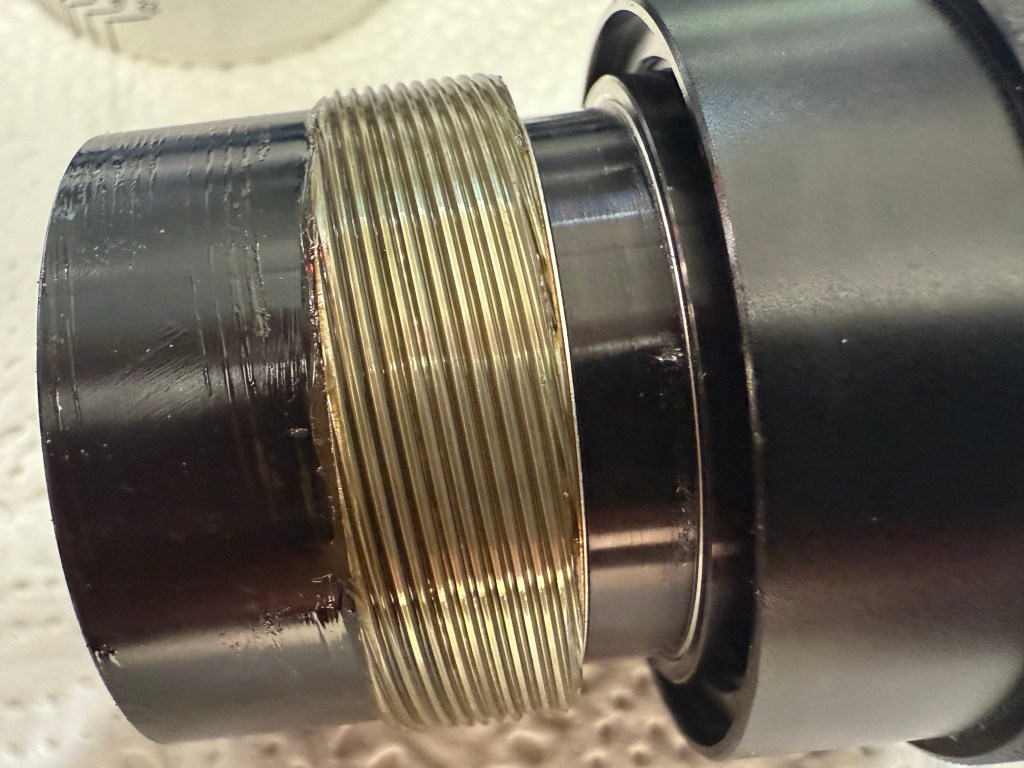

Finally, the aperture housing can be separated from the focusing mechanism. However, before you disengage the helicoids, it’s absolutely critical to mark the exact point of separation. A small scratch or reference line will ensure you maintain the correct orientation during reassembly. Without this, you risk misaligning the helicoids—since they can thread together in multiple configurations, but only one will restore proper focus calibration. Skip this step, and you’re in for a frustrating reassembly process.

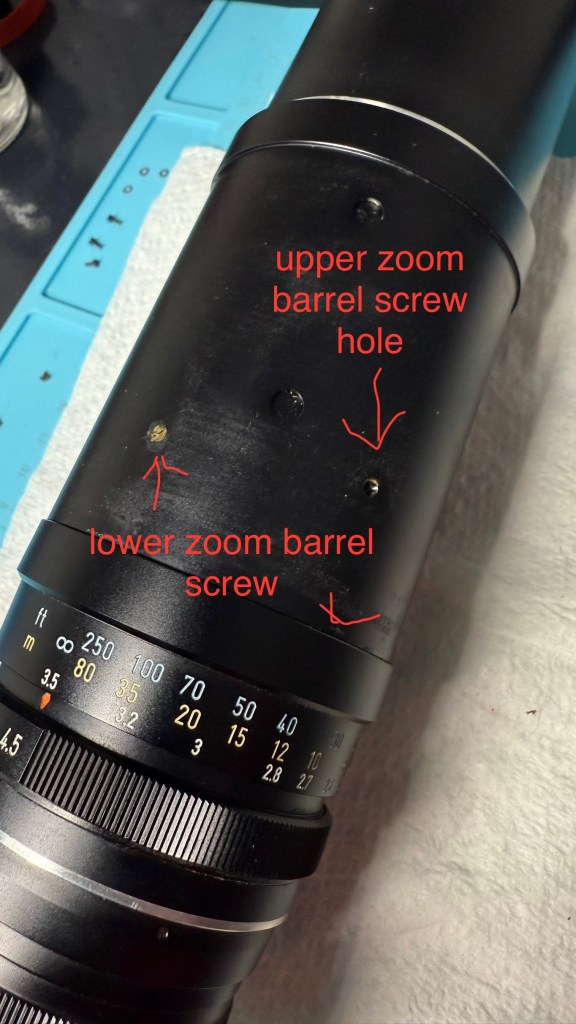

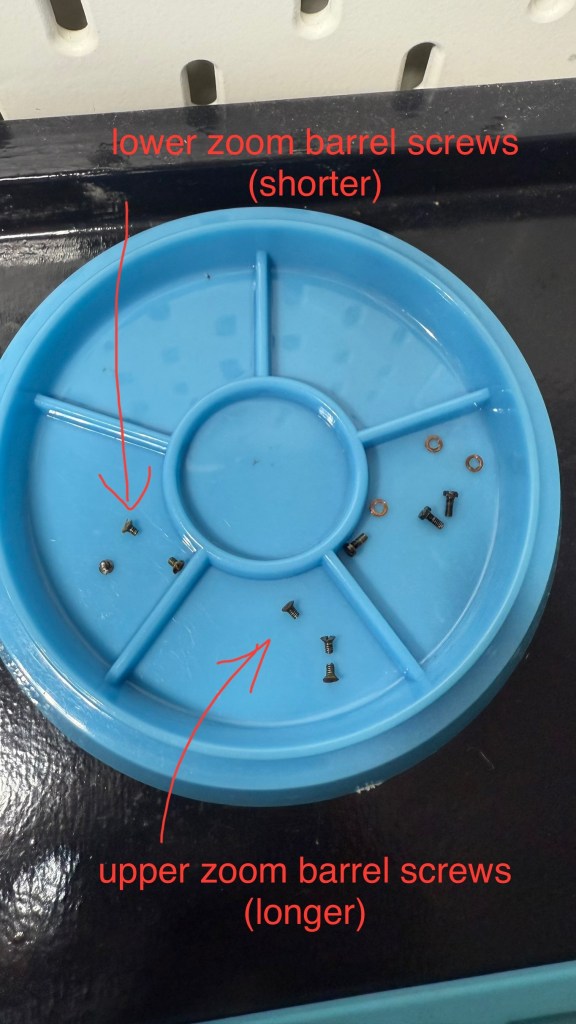

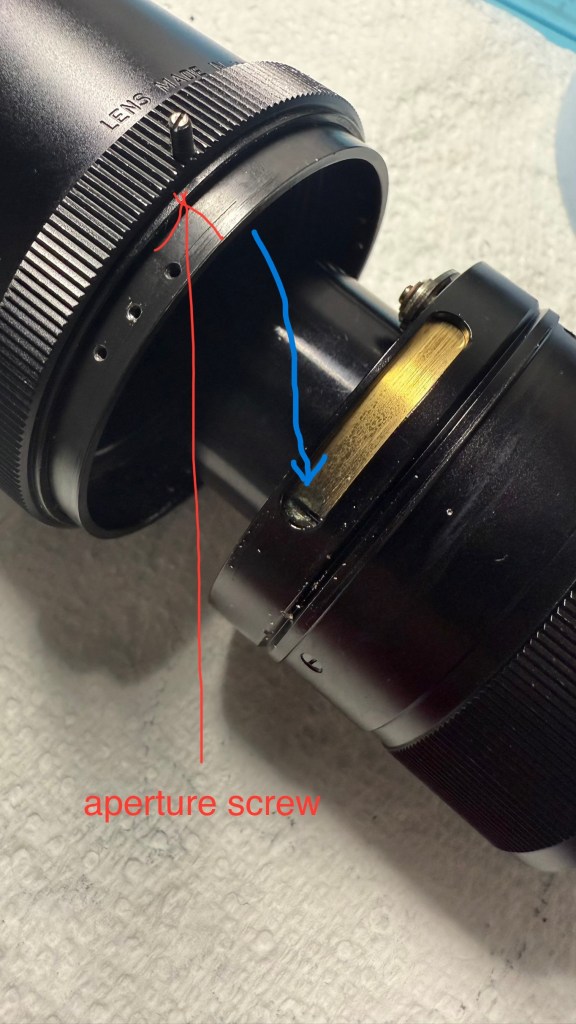

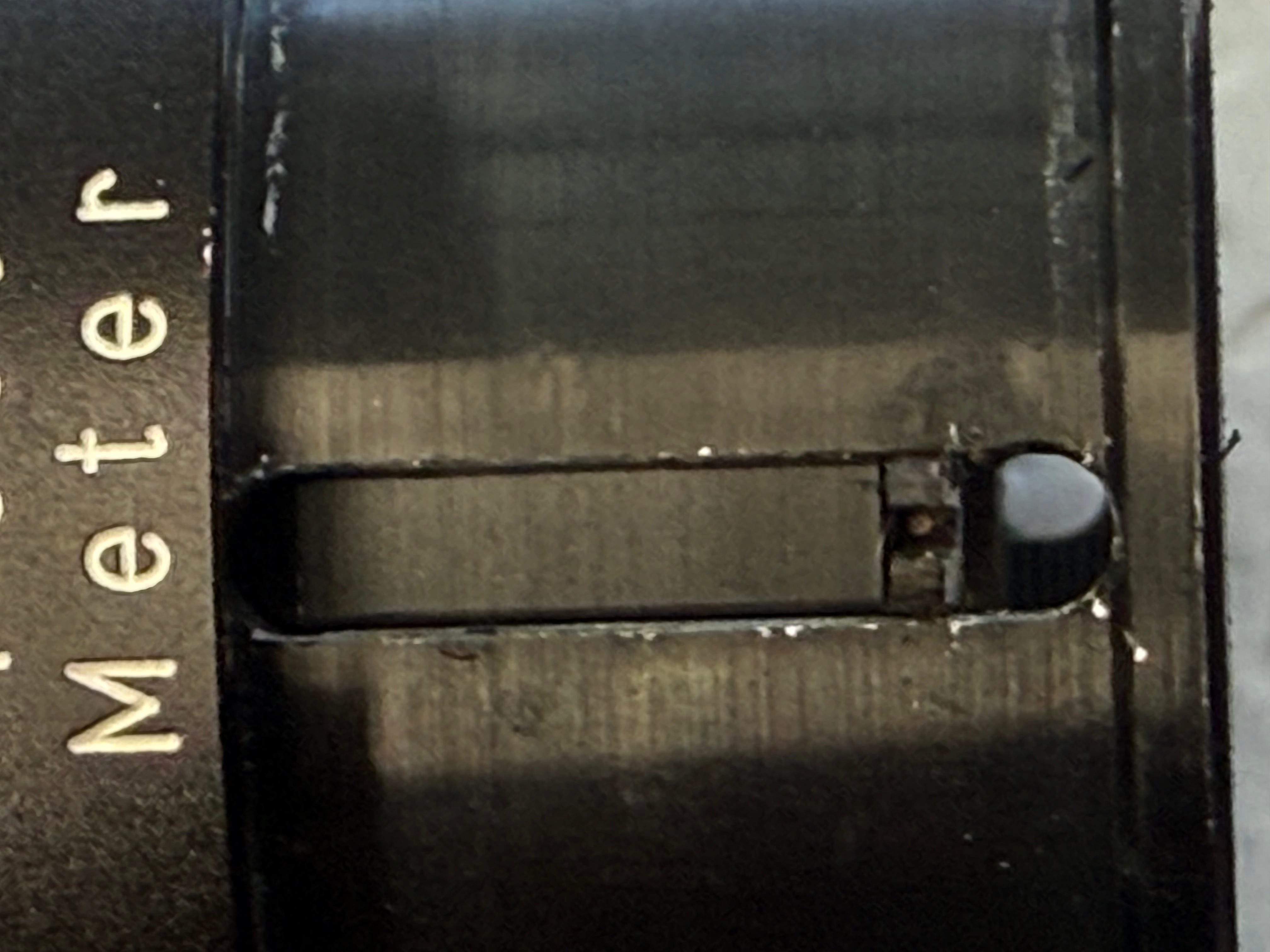

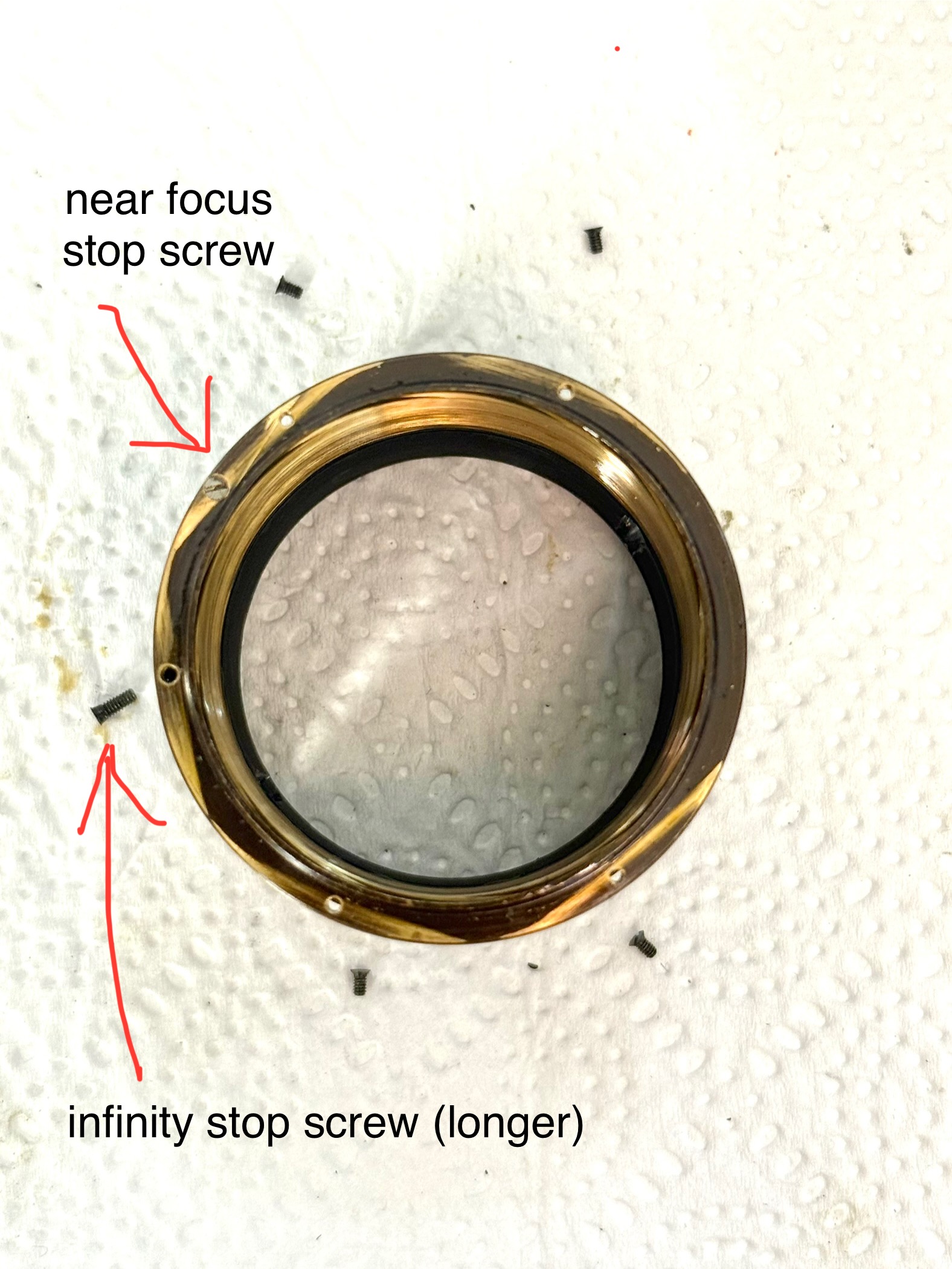

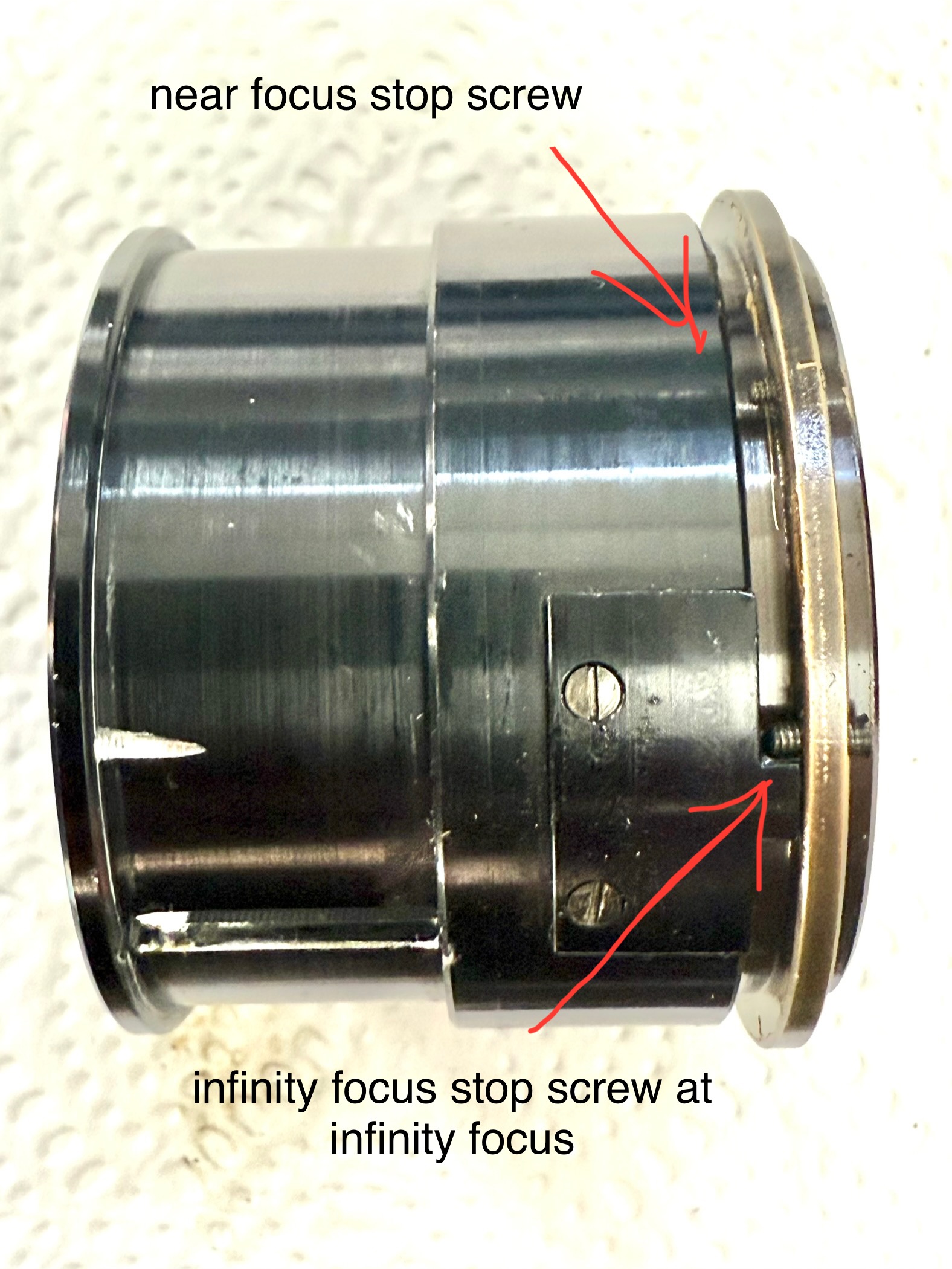

Next, you can remove the distance scale ring. It’s secured by five screws positioned on the inner side of the ring. Pay special attention to the middle screw—it’s longer than the others and also functions as the mechanical stop for infinity focus. Before removing it, make sure to note its exact position when the distance scale is set to infinity. This reference will be crucial for restoring accurate focus during reassembly.

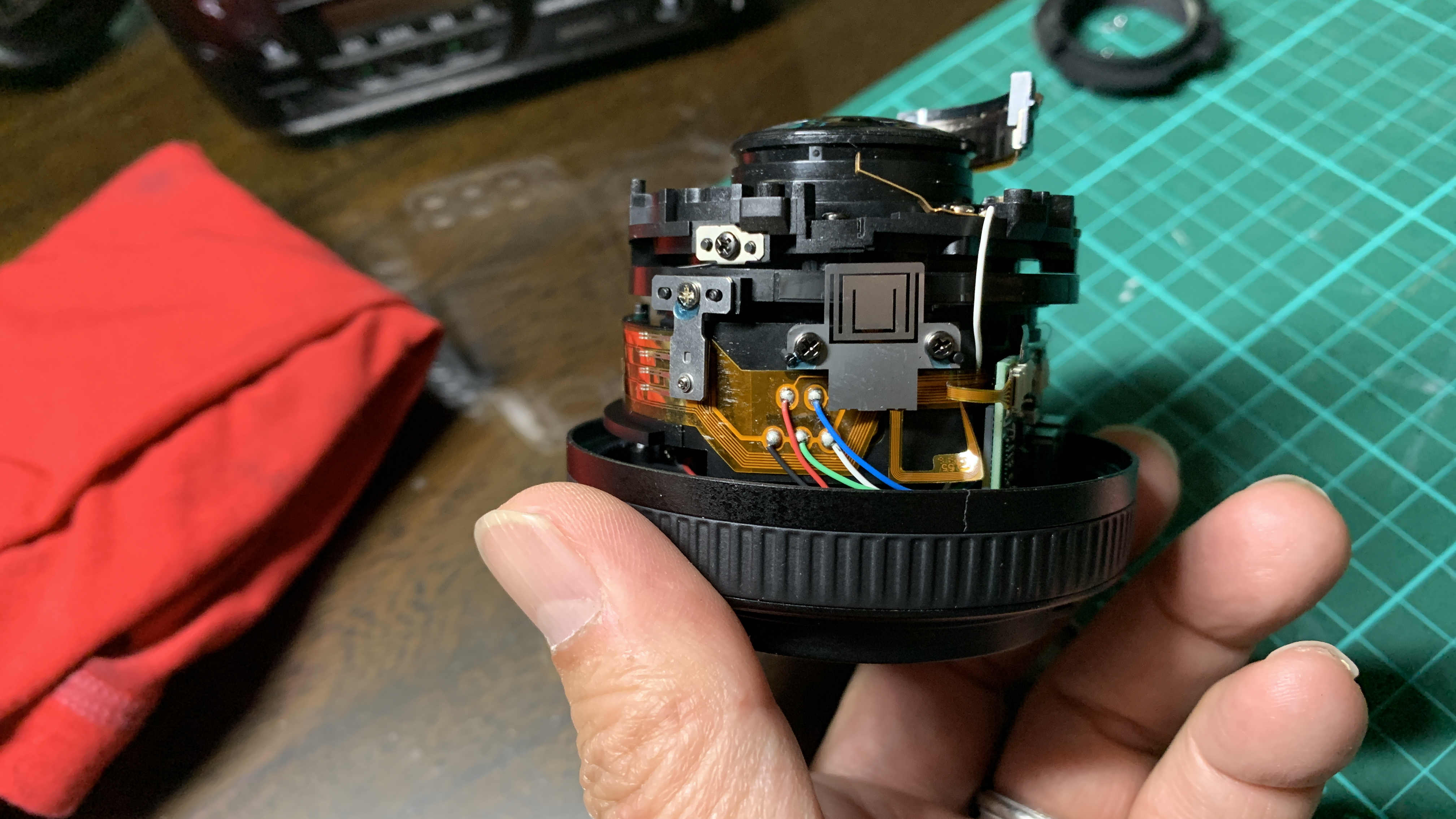

Once the distance scale ring is removed, the orientation of the screws becomes clearly visible. At this stage, you’ll also notice a sixth screw—the near-focus stop screw—revealed after the focusing ring is taken off. It’s important to carefully note its position relative to the infinity stop screw, as both play a crucial role in defining the lens’s focusing range. Marking or photographing their alignment before disassembly can save a lot of guesswork during reassembly and help maintain accurate focus calibration.

Remove the near focusing stop screw and the brass helicoid ring can be rotated out.

After thoroughly cleaning and relubricating the helicoids, reassembly was smooth and uneventful. Everything clicked back into place with satisfying precision—no surprises, no fuss.

Thanks for reading, and I hope this walkthrough helps fellow vintage lens enthusiasts breathe new life into their classic gear!